Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a painful viral infection that affects millions of people worldwide. While it is most common in older adults, anyone who has had chickenpox is at risk of developing shingles later in life. Understanding the symptoms, causes, and available treatments for shingles is crucial for those who may be affected by this condition.

This comprehensive guide will provide an in-depth look at what shingles is, including its characteristic rash and other symptoms. We will explore the underlying causes of shingles and how it is diagnosed. Additionally, we will discuss the various treatment options available to manage the pain and discomfort associated with shingles, as well as potential complications that may arise. Finally, we will cover prevention strategies, including vaccination, to help reduce the risk of developing shingles.

What is Shingles?

Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a viral infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus, the same virus responsible for chickenpox. After an individual recovers from chickenpox, the virus remains dormant in the body, residing in the nervous system. Years or even decades later, the virus may reactivate, causing shingles.

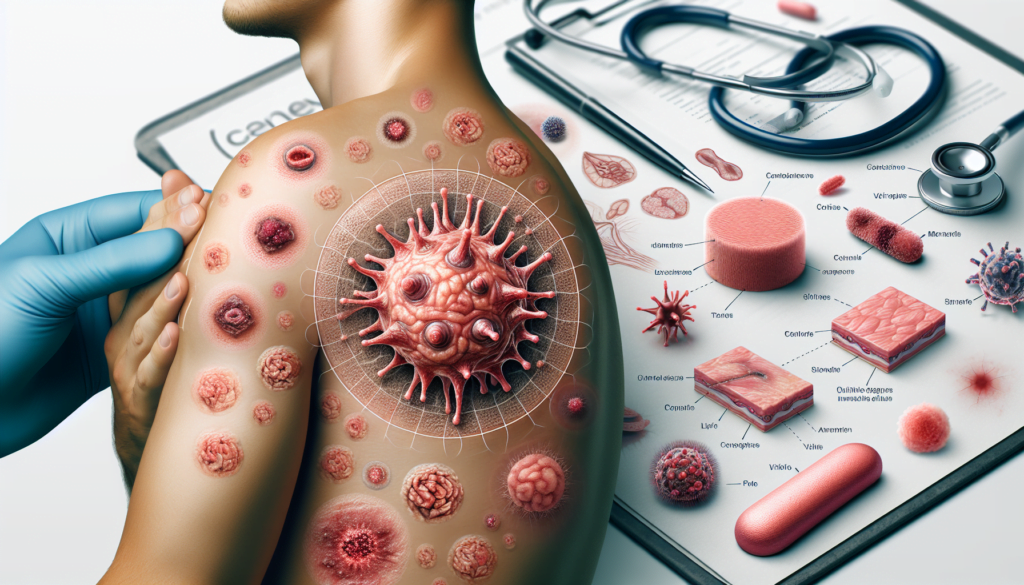

Shingles typically manifests as a painful rash that appears on one side of the body, often in a single stripe that wraps around either the left or right side of the torso. The rash begins as a cluster of small, red, fluid-filled blisters that eventually burst and crust over. The appearance of these blisters may vary depending on skin tone, ranging from red or pink to grayish, purple, or brown.

In addition to the characteristic rash, shingles can cause other symptoms such as fever, headache, chills, and fatigue. Some individuals may experience pain, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected area before the rash appears. This pain can be intense and may be mistaken for other conditions, such as heart, lung, or kidney problems, depending on the location of the pain.

Shingles is most common in older adults, particularly those over the age of 50. However, anyone who has had chickenpox is at risk of developing shingles. Individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or those undergoing immunosuppressive treatments, are at a higher risk of developing shingles.

While shingles itself is not contagious, a person with active shingles can spread the varicella-zoster virus to someone who has never had chickenpox or received the chickenpox vaccine. In such cases, the exposed individual would develop chickenpox, not shingles. Transmission occurs through direct contact with the open sores of the shingles rash, and the risk of spreading the virus is highest when the blisters are present and have not yet crusted over.

Although shingles is rarely life-threatening, it can cause significant discomfort and lead to complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia, a condition characterized by persistent pain even after the rash has healed. Early diagnosis and treatment with antiviral medications can help shorten the duration of the illness and reduce the risk of complications.

Symptoms of Shingles

The symptoms of shingles typically develop in stages and can vary from person to person. The most common symptoms include pain, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected area, followed by the appearance of a characteristic rash.

Early Symptoms

Before the shingles rash appears, people may experience pain, itching, or tingling in the area where the rash will develop. This early warning sign can occur several days before the rash becomes visible. Some individuals describe the sensation as an “electrical” or “burning” feeling on their skin. Other early symptoms may include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Chills

- Fatigue

- Stomach upset

Symptoms during Rash Appearance

The shingles rash usually appears within 1-5 days after the initial symptoms begin. The rash typically manifests as a stripe of blisters that wraps around either the left or right side of the torso, although it can also occur on one side of the face, neck, or other parts of the body. The appearance of the rash may vary depending on skin tone:

| Skin Tone | Rash Appearance |

|---|---|

| Lighter | Red or pink blisters |

| Darker | Grayish, purple, or brown blisters |

The fluid-filled blisters can be painful and may break open, crust over, and eventually scab over in 7-10 days. The rash typically clears within 2-4 weeks.

Other Symptoms

In addition to the rash and early symptoms, some people with shingles may experience:

- Sensitivity to touch in the affected area

- Itching

- Sensitivity to light

- Vision problems (if shingles occur near the eye)

- Difficulty moving facial muscles (if shingles affect the face)

It is crucial to seek medical attention as soon as shingles symptoms appear, especially if the rash develops near the eye, as this can lead to permanent eye damage. Early treatment with antiviral medications can help reduce the severity and duration of the illness, as well as decrease the risk of complications such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Diagnosis of Shingles

Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, can usually be diagnosed based on the characteristic rash and associated symptoms. However, in some cases, additional tests may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis, especially if the presentation is atypical or the patient is immunocompromised.

Physical Examination

During a physical exam, the healthcare provider will carefully examine the skin for the presence of the shingles rash. The rash typically appears as a stripe of blisters on one side of the body or face, often in a dermatomal pattern. The provider will also assess the patient for other symptoms such as pain, itching, or tingling sensations in the affected area.

In some cases, the rash may be widespread or affect multiple dermatomes, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems. Shingles on the face can involve the eye and lead to vision loss, making prompt diagnosis and treatment crucial.

Laboratory Testing

While laboratory tests are not always necessary for diagnosing shingles, they can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis, especially in atypical cases or when the rash is absent. The most common laboratory tests for shingles include:

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): PCR is the most sensitive and specific test for detecting varicella-zoster virus (VZV) DNA. It can be performed on samples collected from skin lesions, such as vesicular fluid, crusts, or scabs. PCR is particularly useful for confirming breakthrough cases in vaccinated individuals and can distinguish between wild-type and vaccine-strain VZV.

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Test: The DFA test is another method for detecting VZV in skin lesion samples. While it is less sensitive than PCR, it is still specific and can provide rapid results. However, due to its lower sensitivity, DFA is not as widely used as PCR.

- Viral Culture: Viral culture involves growing the virus from skin lesion samples in a laboratory setting. Although it is specific for VZV, viral culture is less sensitive and takes longer to yield results compared to PCR. It requires the presence of active, “live” virus in the sample.

Serologic tests, such as VZV IgM and IgG antibody tests, are not routinely recommended for diagnosing acute shingles infections. However, they can be useful in certain situations:

- A four-fold or greater rise in VZV IgG antibody titer between acute and convalescent sera can confirm a current VZV infection.

- VZV IgM antibody tests, while not highly reliable, can sometimes indicate an acute VZV infection when positive in the presence of characteristic symptoms.

In most cases, a thorough physical examination and assessment of clinical symptoms are sufficient to diagnose shingles. Laboratory tests serve as valuable tools for confirming the diagnosis in atypical presentations or when the diagnosis is uncertain.

Treatment Options

There are several treatment options available for managing shingles and its associated symptoms. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce the severity and duration of the illness, alleviate pain, and prevent complications. Treatment typically involves a combination of antiviral medications, pain management, and home remedies.

Antiviral Medications

Antiviral medications are the cornerstone of shingles treatment. These drugs can help slow down the progression of the rash, especially if taken within the first 72 hours of symptom onset. Antiviral medications can also reduce the risk of complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Pain Management

Shingles can cause significant pain and discomfort. Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or naproxen, can help alleviate milder pain. These medications may also help prevent postherpetic neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that can occur after the shingles rash has healed.

For more severe pain, your doctor may prescribe:

- Capsaicin cream (apply with caution and avoid contact with eyes)

- Numbing agents, such as lidocaine, available as creams, lotions, patches, powders, or sprays

- Tricyclic antidepressants, like desipramine (Norpramin), or nortriptyline (Pamelor), which can help manage pain and address any accompanying depression

- Anticonvulsants, such as (Horizant)

In some cases, corticosteroid injections or nerve blocks may be considered for severe pain relief.

Home Remedies

In addition to medical treatments, several home remedies can help manage shingles symptoms and promote healing:

- Cool compresses: Applying a cool, damp cloth to the affected area for about 20 minutes at a time can help relieve itching and discomfort.

- Oatmeal baths: Soaking in a cool bath with colloidal oatmeal can help soothe the skin and reduce itching.

- Calamine lotion: Applying calamine lotion to the rash can provide a cooling, soothing effect and help dry out blisters.

- Loose, breathable clothing: Wearing loose-fitting, natural fiber clothing can help minimize irritation and discomfort.

- Stress management: Practicing relaxation techniques, such as meditation, deep breathing, or gentle exercises like yoga or tai chi, can help reduce stress and promote overall well-being.

It is essential to keep the affected area clean and dry to prevent secondary bacterial infections. Avoid scratching or bursting blisters, as this can lead to further irritation and potential scarring.

While home remedies can provide relief, they should not replace medical treatment. Always consult with your healthcare provider for proper diagnosis and treatment of shingles.

Complications of Shingles

Shingles can lead to several complications, some of which can be severe and long-lasting. The most common complication is postherpetic neuralgia, which causes persistent pain even after the shingles rash has healed. Other potential complications include vision loss and neurological issues.

Postherpetic Neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is the most common complication of shingles, affecting about 1 in 5 people who develop the condition. PHN is characterized by persistent pain that lasts for months or even years after the shingles rash has resolved. The pain can be described as burning, sharp, or stabbing and may be accompanied by itching, tingling, or numbness in the affected area.

Risk factors for developing PHN include:

- Advanced age (over 60 years old)

- Severe pain during the initial shingles outbreak

- A weakened immune system due to underlying health conditions or immunosuppressive treatments

- Delayed treatment of shingles with antiviral medications

Treatment options for PHN include pain medications, topical treatments, and other therapies such as TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) and cold packs.

Vision Loss

Shingles that affect the eye, known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus, can cause severe complications and potentially lead to vision loss. When the virus infects the nerves around the eye, it can cause inflammation and damage to the cornea, retina, and other eye structures.

Complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus may include:

- Corneal scarring

- Uveitis (inflammation of the eye’s middle layer)

- Glaucoma

- Retinal necrosis

Prompt treatment with antiviral medications and close monitoring by an ophthalmologist are essential to minimize the risk of vision loss and other eye-related complications.

Neurological Issues

In rare cases, shingles can lead to neurological complications affecting the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves. These complications may include:

- Meningitis or encephalitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord or inflammation of the brain itself.

- Myelitis: Inflammation of the spinal cord, which can cause weakness, sensory changes, and bowel or bladder dysfunction.

- Cranial nerve palsies: Weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles, leading to drooping eyelids, difficulty moving the eyes, or facial drooping.

- Peripheral nerve damage: Damage to the nerves outside the brain and spinal cord, causing weakness, numbness, or tingling in the affected areas.

These neurological complications require prompt medical attention and treatment to prevent long-term consequences and promote recovery.

Prevention and Vaccination

The most effective way to prevent shingles is through vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that adults 50 years and older get two doses of the shingles vaccine called Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine) to prevent shingles and its complications. Adults 19 years and older who have weakened immune systems due to disease or therapy should also get two doses of Shingrix, as they have a higher risk of getting shingles and related complications.

Available Vaccines

Shingrix is the only FDA-approved vaccine available in the U.S. that provides protection against shingles. It is a non-live vaccine that contains a part of the varicella-zoster virus, which helps the body build a strong defense against the disease. Shingrix is given as a shot in the upper arm, typically administered by a doctor or pharmacist.

Shingrix has been shown to be highly effective in preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), the most common complication of shingles. In adults 50 years and older with healthy immune systems, Shingrix is more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and PHN. The vaccine provides strong protection for at least the first 7 years after vaccination. In adults with weakened immune systems, studies show that Shingrix is 68%-91% effective in preventing shingles, depending on the condition affecting the immune system.

Who Should Get Vaccinated

The CDC recommends that the following groups get vaccinated with Shingrix:

- Adults 50 years and older, regardless of whether they have had shingles or received the previous shingles vaccine.

- Adults 19 years and older who have or will have weakened immune systems due to disease or therapy

The two doses of Shingrix should be separated by 2 to 6 months. For people with weakened immune systems who would benefit from a shorter vaccination schedule, the second dose can be administered 1 to 2 months after the first.

It is important to note that even if you have had shingles in the past, you can still receive Shingrix to help prevent future occurrences. There is no specific waiting period required after having shingles before getting vaccinated, but it is generally recommended to wait until the shingles rash has disappeared.

While Shingrix is highly effective, it is still possible to develop shingles after vaccination. However, the vaccine may reduce the severity and duration of the illness, as well as the risk of complications such as postherpetic neuralgia.

If you have any questions or concerns about getting vaccinated against shingles, consult with your healthcare provider to determine the best course of action for your individual needs.

Conclusion

Shingles is a painful and potentially debilitating condition that affects millions of people worldwide. By understanding the symptoms, causes, and available treatments, individuals can take proactive steps to manage the illness and reduce the risk of complications. Seeking prompt medical attention and following a comprehensive treatment plan are crucial for alleviating discomfort and promoting recovery.

Vaccination remains the most effective way to prevent shingles and its complications. With the highly effective Shingrix vaccine now available, adults 50 years and older, as well as those with weakened immune systems, have a powerful tool to protect themselves against this painful condition. By prioritizing vaccination and maintaining open communication with healthcare providers, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of developing shingles and enjoy a better quality of life.