The ascending aortic aneurysm, a complex condition that marks the enlargement of the upper section of the aorta, stands as a substantial challenge in cardiovascular health. Its significance stems not only from the vital role the aorta plays in circulating blood throughout the body but also from the silent nature of the condition; many individuals remain asymptomatic until a critical event occurs. Understanding the early signs, risks, and available treatments for this condition is crucial for the timely intervention and management of patients at risk. With advancements in medical science, particularly in the areas of diagnosis and surgical intervention, the landscape of management for ascending aortic aneurysm has evolved, offering hope and improved outcomes for those affected.

This article will traverse the spectrum of ascending aortic aneurysm, from its definition and epidemiological impact to the clinical presentation that healthcare providers may encounter. Further, it will delve into the pathology underlying the condition, guiding readers through the latest in diagnosis and imaging techniques that are critical for a timely and accurate identification. Treatment methodologies, including ascending aortic aneurysm repair and the criteria for determining the best hospital for ascending aortic aneurysm surgery, will be explored in depth. Additionally, the article will discuss ascending aortic aneurysm guidelines for treatment, offering insights into the current standards of care and prognostic expectations for patients. By consolidating this information, the article aims to provide a comprehensive overview that enriches understanding and supports the clinical management of ascending aortic aneurysm.

What is an Ascending Aortic Aneurysm?

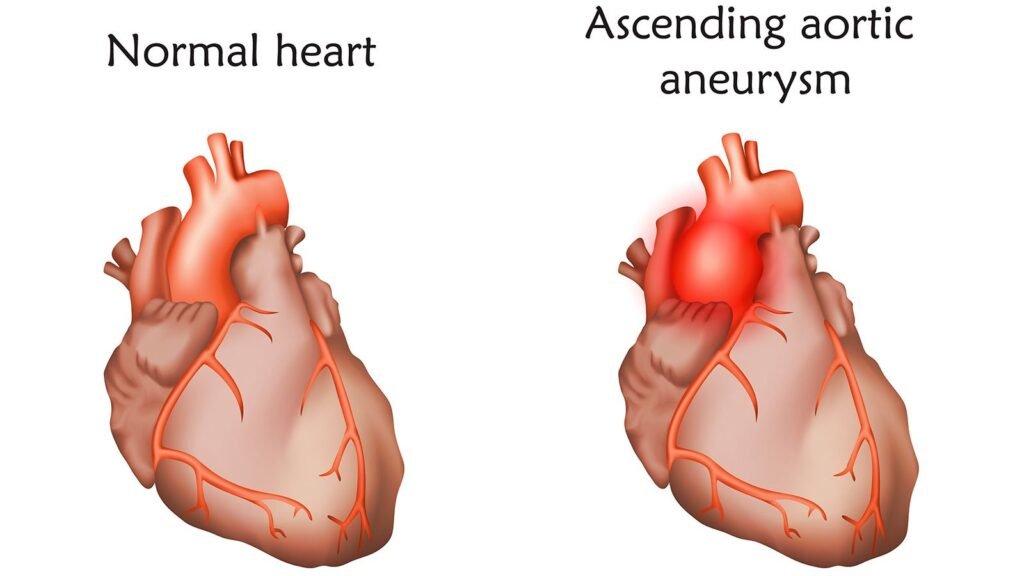

An ascending aortic aneurysm is characterized by a dilation of the ascending aorta, which is the initial segment of the aorta, the main artery that carries blood away from the heart to the rest of the body. This condition is identified when the diameter of the ascending aorta expands to at least 1.5 times its normal size, typically defined as 5 cm or more in individuals under 60 years old, or when any diameter reaches 4 cm or more.

Ascending aortic aneurysms are classified as either true or false aneurysms. True aneurysms involve all three layers of the arterial wall (intima, media, and adventitia) and can develop due to various conditions including genetic connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Other causes include inflammatory conditions like aortitis, infections such as syphilis, and degenerative diseases that lead to cystic medial degeneration of the aortic wall. Additionally, conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and bicuspid aortic valve can also predispose individuals to this type of aneurysm.

On the other hand, false aneurysms, or pseudoaneurysms, occur when there is a breach in the arterial wall leading to blood leakage that is contained by surrounding tissues. These are often the result of trauma, such as deceleration injuries, or complications from previous surgeries on the thoracic aorta.

The ascending aorta itself consists of two main parts: the aortic root, which includes the sinuses of Valsalva and the sinotubular junction, and the tubular ascending aorta, extending from the sinotubular junction to the aortic arch. The entire segment is crucial for the proper function of the aortic valve and the efficient delivery of blood to the upper body.

Ascending aortic aneurysms are the most common subtype of thoracic aortic aneurysms, affecting about 60% of cases. Despite their prevalence, they often remain asymptomatic until they become large enough to cause noticeable symptoms or lead to life-threatening complications such as dissection or rupture, which can result in severe internal bleeding. The condition is identified incidentally in many cases during imaging studies conducted for other reasons.

Overall, the management and prognosis of ascending aortic aneurysms depend significantly on early detection and the underlying causes. As such, understanding the anatomy, etiology, and potential risks associated with this condition is essential for appropriate monitoring and intervention.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Ascending aortic aneurysms (ATAAs) are a significant health concern, affecting approximately 10 out of every 100,000 people annually. The prevalence of this condition underscores its impact on public health, particularly given its potential for severe complications such as dissection or rupture if left undetected and untreated. Studies indicate that about 60% of all thoracic aortic aneurysms involve the ascending aorta, highlighting the importance of this subtype in cardiovascular diseases.

Research shows varied prevalence rates across different demographics and regions. For instance, in a middle-aged Swedish population, the prevalence of aortic aneurysm dilation was found to be 1.4%. However, other studies have reported higher rates, with one indicating a prevalence of 23% in a group undergoing diagnostic coronary CT angiography (CCTA). These discrepancies may be attributed to factors such as age, smoking habits, and the presence of hypertension.

Risk Factors

The development of ATAA is influenced by a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Key risk factors include:

- Age and Gender: Men are more frequently affected by ATAA, particularly those in their sixth and seventh decades of life. Women, while less commonly affected, tend to be diagnosed later, leading to potentially worse outcomes.

- Genetic Conditions: Several familial or genetic conditions increase the risk for ATAA, including Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Loeys–Dietz syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Turner syndrome, and familial thoracic aortic aneurysms. Additionally, a bicuspid aortic valve, which is an abnormal aortic valve, significantly raises the risk.

- Lifestyle Factors: Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor, particularly for abdominal aortic aneurysms. It can accelerate the growth of aneurysms and increase the likelihood of rupture. Other lifestyle factors include the use of stimulants like cocaine, which raises blood pressure and subsequently the risk of aneurysms.

- Medical Conditions: Several medical conditions are linked to the increased risk of developing ATAA. These include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular conditions like atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, and conditions that cause increased arterial stiffness such as high pulse wave velocity (PWV).

- Ethnicity and Racial Background: There are notable differences in the prevalence of aortic aneurysms among different ethnic groups. For example, abdominal aortic aneurysms are less common among Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian Americans compared to other populations.

Understanding these risk factors is crucial for the early detection and management of ATAA, potentially reducing the incidence of severe complications such as dissection or rupture.

Clinical Presentation

Common Symptoms

Most individuals with ascending aortic aneurysms do not exhibit any symptoms, making the condition challenging to detect without specific diagnostic procedures. However, when symptoms do manifest, they may include:

- Chest pain or pain high in the back, which could indicate pressure or growth of the aneurysm.

- Coughing or wheezing, potentially caused by the aneurysm exerting pressure on the respiratory pathways.

- Difficulty swallowing, which occurs if the expanding aneurysm compresses the esophagus.

- Hoarseness, a result of pressure on the vocal cords or nerve damage.

- Shortness of breath, which can arise from compression of the lungs or airways.

For individuals experiencing these symptoms, it is crucial to seek medical evaluation to determine if an ascending aortic aneurysm is the underlying cause.

Signs of Rupture

The rupture of an ascending aortic aneurysm is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate medical attention. Symptoms indicative of a rupture or dissection include:

- Sudden, severe, and sharp pain in the chest or upper back, which may spread downward. This pain is often described as tearing, stabbing, or ripping.

- Difficulty breathing, which can signify that the aneurysm is affecting lung function or airway integrity.

- Low blood pressure, which may lead to shock and is indicative of severe internal bleeding.

- Loss of consciousness, dizziness, or stroke symptoms, suggesting that the aneurysm may be interfering with blood flow to the brain.

- Confusion, trouble speaking, or vision loss, which are critical signs that require immediate intervention.

Recognizing these symptoms and understanding their severity is vital for prompt diagnosis and treatment, potentially saving lives and improving outcomes for those affected by this serious condition.

Pathology

Definition and Criteria

An ascending aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a dilation of the ascending segment of the aorta, which is the major artery exiting the heart. This condition is classified when the aorta’s diameter expands to at least 1.5 times its normal size. The typical threshold for concern is a diameter exceeding 5 cm in individuals under 60 years old or when any diameter reaches 4 cm or more. Aneurysms may present as true aneurysms involving all three layers of the arterial wall—intima, media, and adventitia—or as false aneurysms, where a breach in the arterial wall leads to blood leakage contained by surrounding tissues.

Causes and Etiology

The etiology of ascending aortic aneurysms is multifactorial, involving genetic, degenerative, and inflammatory pathways that weaken the aortic wall.

- Genetic Factors: Disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome are caused by mutations that affect the body’s connective tissues, particularly those that make up the aortic wall. These conditions lead to weakening of the vessel wall and predispose individuals to aneurysms. Familial patterns of aortic aneurysms also suggest a strong genetic component, with mutations in genes like MYH11 and ACTA2 being implicated.

- Degenerative Changes: Over time, the aortic media can undergo degenerative changes known as cystic medial degeneration. This process involves the loss of elastic fibers and smooth muscle cells, which are critical for the aortic wall’s structural integrity. Such degeneration is often accelerated by factors like hypertension and atherosclerosis, although it can also occur as a part of normal aging.

- Inflammatory Conditions: Aortitis, which includes conditions such as giant cell arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis, can cause inflammation of the aortic wall, leading to weakening and eventual dilation. Additionally, infections such as syphilis historically led to aneurysm formation through inflammatory damage, though this is less common in contemporary medical settings.

- Physical Stress and Trauma: Traumatic injuries to the chest can lead to the development of false aneurysms. Conditions such as a bicuspid aortic valve also create abnormal hemodynamic stresses that contribute to the dilation of the ascending aorta.

Understanding the complex interplay of these factors is crucial for the management and treatment of ascending aortic aneurysms, aiming to prevent life-threatening complications such as dissection or rupture.

Diagnosis and Imaging

Imaging tests play a crucial role in the diagnosis and management of ascending aortic aneurysms (ATAAs), providing detailed insights into the size, shape, and potential complications of aneurysms. Various imaging modalities are employed to achieve a comprehensive evaluation.

Chest X-Ray

Chest radiographs are often the initial imaging technique used in the evaluation of patients suspected of having thoracic aneurysms. While they can show a widened mediastinum or other changes suggestive of an aneurysm, the findings are generally nonspecific. Approximately 80-90% of patients with thoracic aneurysms display abnormalities on chest X-rays, such as mediastinal widening, which occurs in more than 75% of cases. However, these signs can be difficult to differentiate from other conditions like aortic tortuosity associated with long-standing hypertension. The sensitivity of chest X-rays for overt aortic dissection is about 64%, with a specificity of 86%, indicating that while useful, they cannot definitively rule out acute aortic conditions on their own.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram (TTE)

TTE is a non-invasive ultrasound method that uses sound waves to create images of the heart and aorta. It is particularly useful for assessing the aortic root and proximal ascending aorta. The technique provides valuable information about the heart’s function and the aorta’s structure but has limitations in visualizing the entire aorta, especially the descending thoracic aorta. For more detailed examination, especially in cases of suspected aortic dissection, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is preferred due to its superior image quality and ability to visualize a larger portion of the thoracic aorta.

CT/MRI

Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are critical tools for the detailed assessment of aortic aneurysms. CT scans, particularly when used with contrast, can rapidly provide precise information about the size, shape, and extent of an aneurysm, as well as its relationship to nearby structures. This modality is especially useful for diagnosing aortic dissection, with CT angiography being the preferred method for evaluating suspected cases due to its high sensitivity and specificity.

MRI, including MR angiography (MRA), offers excellent visualization of the aortic anatomy without the use of ionizing radiation. It is highly accurate in determining the location and size of aneurysms and is particularly beneficial for patients with preexisting aortic disease. MRI is also advantageous for following up on known aneurysms and assessing the aorta’s branches.

Together, these imaging modalities provide a comprehensive toolkit for the accurate diagnosis and management of ascending aortic aneurysms, facilitating timely and effective treatment interventions.

Treatment and Prognosis

Medications

Medications play a crucial role in managing ascending aortic aneurysm (AAA) by targeting the underlying risk factors and slowing the progression of the disease. For patients with conditions like hypertension and dyslipidemia, which are significant risk factors for aneurysm formation, a rigorous regimen of antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering medications is essential. Beta blockers are commonly prescribed to reduce blood pressure and the rate of aortic dilation, particularly in patients with genetic conditions like Marfan syndrome. Angiotensin II receptor blockers may be recommended for individuals who cannot tolerate beta blockers or in cases like Loeys-Dietz syndrome, even if high blood pressure is not present. Statins are also used to manage cholesterol levels, helping to prevent atherosclerosis, a major contributor to aneurysm complications.

Surgical Interventions

Surgical repair remains the definitive treatment for large or symptomatic ascending aortic aneurysms. The decision to operate is typically based on the aneurysm’s size, growth rate, and the patient’s overall health and genetic factors. Surgery involves removing the dilated segment of the aorta and replacing it with a synthetic graft. This procedure may also entail the repair or replacement of the aortic valve if it is affected. Two primary surgical approaches are used:

- Open Surgery: This traditional method involves a chest incision to access the aorta directly. It requires the use of cardiopulmonary bypass and may involve reattaching coronary arteries if they are impacted by the aneurysm or its repair.

- Endovascular Surgery: A less invasive option, this involves inserting a graft through a catheter in the groin and maneuvering it into place within the aorta. This method is not suitable for all patients, particularly when the aneurysm involves the aortic root or ascending aorta.

Patients with specific conditions, such as Marfan syndrome or a bicuspid aortic valve, may require surgery at smaller aneurysm sizes due to the increased risk of rupture. Post-surgical recovery can vary, with most patients requiring four to six weeks for initial recovery, though full recovery may take several months.

Prognosis and Follow-Up

The prognosis for patients with AAA varies significantly based on several factors, including the condition’s severity at diagnosis, the presence of other medical conditions, and the success of surgical intervention. Elective surgery for AAA has high survival rates, with many patients returning to normal life expectancy post-recovery. However, emergency surgery for ruptured or dissected aneurysms carries a higher risk, with significant mortality rates if not treated promptly.

Long-term follow-up is crucial for all patients, regardless of whether they undergo surgery. This includes regular imaging tests to monitor the aneurysm or the integrity of the surgical repair and adjustments to medications as needed. Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and the management of blood pressure and cholesterol, are also vital to improving outcomes and preventing complications. Regular follow-up appointments help ensure that any changes in the patient’s condition are addressed promptly, thus maintaining the stability of their health post-treatment.

Conclusion

Throughout this comprehensive exploration of ascending aortic aneurysms, we’ve traversed the pathology, risks, clinical presentations, and crucial advancements in diagnostics and treatment that mark the contemporary approach to managing this life-threatening condition. Central to the discussion was the emphasis on early detection and timely intervention, underscored by the silent yet progressive nature of the condition, which often remains asymptomatic until reaching a critical stage. The significance of understanding risk factors, recognizing early signs, and the role of advanced imaging techniques in diagnosis cannot be overstated, as these elements collectively contribute to improving patient outcomes and the overall management of the condition.

In the realm of treatment, the evolution of surgical techniques and the prudent use of medication have both played pivotal roles in extending the life expectancy and enhancing the quality of life for individuals diagnosed with ascending aortic aneurysms. As we continue to advance our understanding and refine our approaches, the importance of patient education, regular monitoring, and targeted research to uncover more effective treatments becomes ever more apparent. It is through these concerted efforts—by patients, healthcare providers, and researchers alike—that we can hope to mitigate the risks associated with this complex condition, moving toward a future where the prognosis for ascending aortic aneurysm patients is brighter than ever before.