Cachexia, also known as wasting syndrome, is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by severe weight loss, muscle wasting, and fatigue. This debilitating condition affects millions of people worldwide, often as a complication of chronic illnesses such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cachexia not only diminishes patients’ quality of life but also reduces their response to treatment and overall survival.

This article takes a deep dive into cachexia, exploring its causes, risk factors, and symptoms. It also examines the impact of cachexia on patients’ quality of life and discusses the diagnostic process. Furthermore, the article delves into the various treatment and management strategies available for individuals suffering from this challenging condition. By providing a comprehensive overview of cachexia, this article aims to increase awareness and understanding of this often-overlooked syndrome.

What is Cachexia?

Cachexia is a complex metabolic syndrome characterized by severe weight loss, muscle wasting, and fatigue that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support. It is often associated with an underlying chronic illness such as cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), HIV/AIDS, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease.

Cachexia involves changes in the way the body uses proteins, carbohydrates, and fat. It is more than just a loss of appetite; people with cachexia may also burn calories faster than usual. They lose both muscle mass and often fat as well.

The cells in the muscles, fat, and liver of individuals with cachexia might not respond well to insulin, a condition known as insulin resistance. This means the body cannot effectively use glucose from the blood for energy. Additionally, in cancer-related cachexia, the immune system releases certain chemicals called cytokines into the blood, causing inflammation. These cytokines contribute to the loss of fat and muscle.

The main symptoms of cachexia include:

- Severe weight loss, including loss of fat and muscle mass

- Loss of appetite

- Anemia (low red blood cell count)

- Weakness and fatigue

Cachexia is more common in people with advanced cancer, particularly lung cancer or cancers of the digestive system. Up to 80% of people with advanced cancer develop some degree of cachexia. It can also occur in the advanced stages of other illnesses such as heart disease, HIV, and kidney disease.

Researchers are working to better understand the causes of cachexia and find new ways to treat it. Some potential treatments being investigated include appetite stimulants, drugs that mimic the hormone ghrelin to improve appetite, and medications that target the inflammatory response. However, more research is needed to fully understand and effectively treat this complex syndrome.

Causes and Risk Factors of Cachexia

Cachexia is a complex metabolic syndrome that can be triggered by various underlying chronic conditions. The major causes of cachexia include cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and chronic infectious and inflammatory diseases such as AIDS. These conditions create an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses in the body, leading to metabolic dysfunction and tissue wasting.

Cancer and Cachexia

Cancer is one of the most common causes of cachexia, with a prevalence ranging from 50% to 90% depending on the type of cancer. Gastrointestinal and lung cancers are most frequently associated with the development of cachexia. Tumor cells secrete factors that activate proteolysis and lipolysis, leading to muscle and fat loss. Additionally, inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor and interleukins, induce anorexia while increasing catabolic hormones like cortisol, and catecholamines, resulting in a hypermetabolic state.

Other Chronic Conditions

Apart from cancer, several other chronic diseases can lead to cachexia:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Chronic heart failure

- Chronic kidney disease

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis

- Diabetes mellitus

In these conditions, the persistent increase in basal metabolic rate, coupled with reduced nutrient intake and increased protein breakdown, contributes to the development of cachexia.

Metabolic and Inflammatory Processes

The pathogenesis of cachexia involves a complex interplay of metabolic and inflammatory processes. Factors involved in this abnormal metabolic cascade include:

- Digestive factors: Poor intake due to dysgeusia, nausea, dysphagia, mucositis, and constipation

- Tumor-mediated factors: Activation of proteolysis and lipolysis

- Inflammatory mediators: Cytokines (tumor necrosis factor, interleukins) inducing anorexia and increasing catabolic hormones (cortisol, catecholamines)

- Hormonal anabolic mediators: Reduced levels of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), testosterone, and ghrelin

These factors collectively contribute to the persistent catabolic state observed in cachexia, leading to muscle wasting, fat loss, and overall metabolic dysfunction.

In summary, cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome caused by various chronic conditions, with cancer being the most common. The complex interplay of metabolic and inflammatory processes, along with tumor-mediated factors and hormonal imbalances, leads to the characteristic muscle wasting and weight loss seen in cachexia patients.

Symptoms of Cachexia

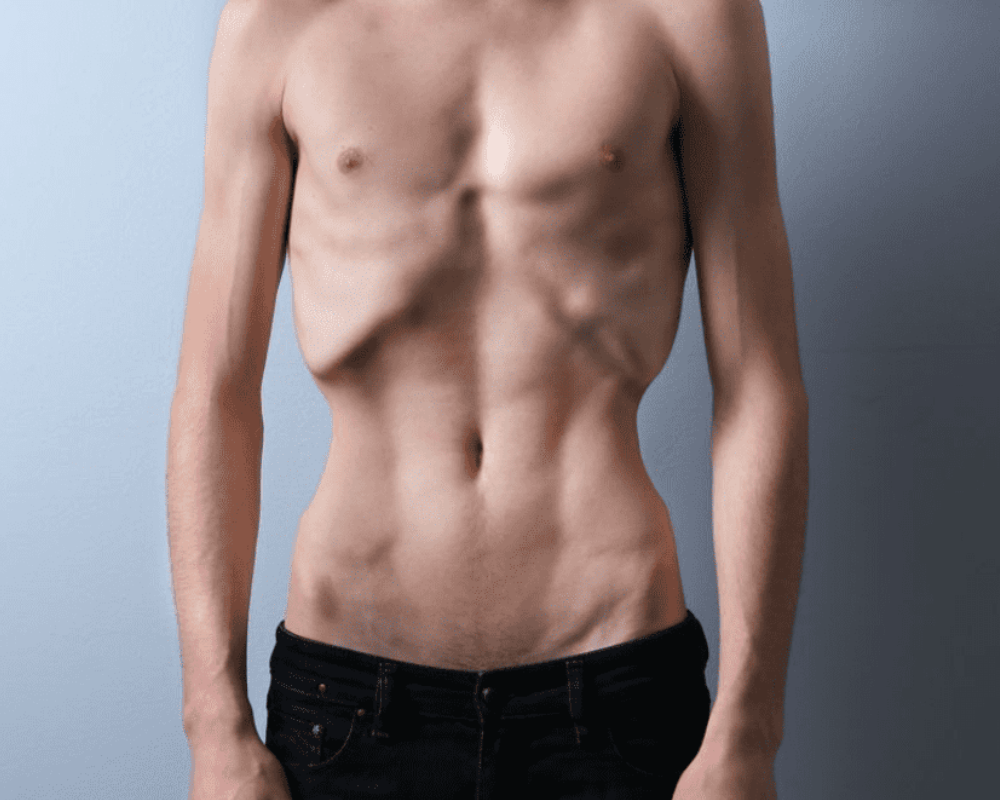

Cachexia causes extreme weight loss and muscle wasting. The main symptoms of cachexia include:

Involuntary Weight Loss

A person may lose weight despite getting adequate nutrition or a high number of calories. This weight loss is non-deliberate and occurs even if the person is eating normally.

Muscle Wasting

This is the characteristic symptom of cachexia. Despite the ongoing loss of muscle, not all people with cachexia appear malnourished. For example, a person who was overweight before developing cachexia may appear to be of average size despite having lost a significant amount of weight.

Loss of Appetite or Anorexia

A person with cachexia may lose their desire to eat any food at all. This loss of appetite contributes to the ongoing weight loss.

Fatigue and Weakness

A person may experience symptoms of malaise, fatigue, and low energy levels. This may include generalized feelings of discomfort, extreme tiredness, or a lack of motivation. The loss of muscle mass leads to reduced functional ability and physical weakness.

Other symptoms that may occur in cachexia include:

- Swelling or edema: Low protein levels in the blood may cause fluid to move into the tissue, causing swelling.

As cachexia is sometimes difficult to recognize, doctors use a variety of criteria for diagnosis. In the most common system, the person must meet two criteria:

- Non-deliberately losing more than 5% of body weight in 12 months or less

- Having a body mass index (BMI) less than 20 kg/m2

Cachexia causes diminished quality of life and loss of the ability to live independently. It also leads to impaired response to treatments, reduced immunity, escalating symptoms of the underlying chronic condition, and a reduced life expectancy from the underlying disease. Treatment of cachexia often depends on its associated underlying condition.

Impact of Cachexia on Patients’ Quality of Life

Cachexia has a profound impact on the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. The physical and psychological effects of this wasting syndrome can be debilitating, affecting multiple aspects of a patient’s well-being.

Physical Health

Cachexia is characterized by significant weight loss, primarily due to the loss of skeletal muscle mass and adipose tissue. This leads to decreased physical function, reduced mobility, and increased fatigue. Patients may experience difficulty performing everyday tasks, such as walking, dressing, and self-care. The loss of muscle strength and endurance can also lead to a higher risk of falls and fractures.

Moreover, cachexia can exacerbate other cancer-related symptoms, such as pain, nausea, and breathlessness. The metabolic changes associated with cachexia can lead to a decreased response to cancer treatments, increased treatment toxicity, and a higher risk of complications. As a result, patients with cachexia often have a poorer prognosis and shorter survival compared to those without the syndrome.

Mental Health

The physical changes and limitations imposed by cachexia can have a significant psychological impact on patients. The visible signs of weight loss and muscle wasting can alter body image and self-esteem. Patients may feel self-conscious about their appearance and withdraw from social interactions.

Depression and anxiety are common among patients with cachexia. The loss of independence, reduced ability to participate in enjoyable activities, and the overall burden of the disease can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and despair. Patients may also experience a sense of loss of control over their bodies and their lives.

Furthermore, the social and emotional impact of cachexia extends to family members and caregivers. Seeing a loved one’s physical decline and the challenges they face can be emotionally distressing. Caregivers may feel helpless and overwhelmed as they try to provide support and manage the practical aspects of care.

In conclusion, cachexia has a significant negative impact on the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. The physical and psychological effects of the syndrome can be devastating, affecting multiple domains of well-being. Addressing the needs of patients with cachexia requires a multidisciplinary approach that focuses on symptom management, nutritional support, physical rehabilitation, and psychosocial interventions to improve overall quality of life.

Diagnosis of Cachexia

The diagnosis of cachexia involves a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s weight loss, body composition, and underlying chronic illness. According to the international consensus definition, cachexia is diagnosed when there is an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support and leads to progressive functional impairment.

Criteria for Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for cachexia include:

- Weight loss greater than 5% over the past 6 months (in absence of simple starvation); or

- BMI less than 20 and any degree of weight loss greater than 2%; or

- Appendicular skeletal muscle index consistent with sarcopenia (males: <7.26 kg/m2; females: <5.45 kg/m2) and any degree of weight loss greater than 2%.

In addition to these criteria, the presence of an underlying chronic disease, such as cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart failure, or chronic kidney disease, is essential for the diagnosis of cachexia.

Diagnostic Tests

Several diagnostic tests can be used to assess body composition and muscle mass in patients with suspected cachexia:

- Bioimpedance analysis (BIA): BIA is a non-invasive method that estimates body composition by measuring the resistance of the body to a small electrical current. It can provide information on fat mass, lean body mass, and total body water.

- Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA): DXA is a more accurate method for measuring body composition, including bone mineral density, fat mass, and lean body mass. It uses low-dose X-rays to differentiate between bone, fat, and lean tissue.

- Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): These imaging techniques can provide detailed information on muscle mass and quality, as well as the distribution of fat tissue. They are particularly useful in assessing sarcopenia and distinguishing between subcutaneous and visceral fat.

In addition to body composition assessments, laboratory tests can help identify underlying metabolic disturbances and inflammation associated with cachexia. These tests may include:

- C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) to assess inflammation

- Albumin and pre-albumin to evaluate nutritional status

- Complete blood count to check for anemia

- Glucose tolerance test or HOMA index to assess insulin resistance

- Testosterone levels in men to evaluate hypogonadism

A comprehensive approach to diagnosing cachexia, including clinical assessment, body composition measurements, and laboratory tests, is essential for identifying patients who may benefit from targeted interventions to prevent further muscle wasting and improve quality of life.

Treatment and Management of Cachexia

The management of cachexia is a complex challenge that should address the different causes underlying this clinical event with an integrated or multimodal treatment approach targeting the different factors involved in its pathophysiology. The treatment of cancer cachexia involves a combination of nutritional interventions, medications and supplements, exercise, and emotional support.

Nutritional Interventions

Nutritional support is a cornerstone of multimodal therapy for cancer cachexia. Optimal nutritional care is pivotal in the treatment, and the effects of nutrients may extend beyond provision of adequate energy intake, targeting different mechanisms or metabolic pathways that are affected or deregulated by cachexia.

Nutritional counseling is a core component of many interventions, with its aim being to increase energy, protein, and/or overall nutrient intake to maintain or increase body weight. Counseling supports protein, energy and nutrient intake according to need, with a target intake potentially being set. Meal plans, education on food preparation, and diet prescriptions may be provided. Common elements include encouraging frequent meals or snacking and increasing the nutritional density of intake by modifying what can be eaten. Tailoring to food preferences and eating habits is also important.

The combination of high quality nutrients in a multitargeted, multinutrient approach appears specifically promising, preferentially as a multimodal intervention, although more studies investigating the optimal quantity and combination of nutrients are needed. Artificial nutrition and supplementation should be implemented when necessary if patients are unable to reach requirements for health and treatment optimization. Supplements should be prescribed under the supervision of a health professional.

Regarding protein intake, the amount and type, there is no clear and concise information or guidelines. However, the authors agree that nutritional status of cancer patients is poor, especially the amount and quality of protein ingested. A minimum range from 1 to 1.2–2 g/kg/day is suggested without specifying the type or time frame of intake.

Medications and Supplements

Several pharmacological agents have been proposed to treat cancer cachexia, but there are currently no approved treatments. Progestagens are currently considered the best available treatment option for cancer cachexia, and they are the only drugs approved in Europe. However, their ability to treat cachexia is limited. Corticosteroids are also widely used and seem equally effective as progestagens, although they have more side effects with long-term use.

Other drugs that have been investigated but failed to show univocal results in clinical trials so far include eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), cannabinoids, and anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibodies. Several emerging drugs have shown promising results but are still under clinical investigation, including selective COX-2 inhibitors, ghrelin mimetics, insulin, oxandrolone.

The ergogenic aids are focused on the implementation of antioxidant, vitamin D and anticatabolic substances such as β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB). HMB supplementation has shown beneficial effects on muscle protein turnover and could be a useful supplement as part of the treatment of muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. However, further exploration of the efficacy of lower doses is required.

Exercise

Regular physical activity holds a promising future as a nonpharmacological alternative to improve patient survival through cachexia prevention. Evidence suggests exercise training is beneficial during cancer treatment and survival. Exercise typically includes resistance training (e.g., stand to sit exercises in the home) and aerobic exercise (e.g., walking) tailored to the individual’s capability with goals set to support engagement and inform personalization of the program. The purpose is to treat inflammatory response, increase muscle mass, increase or maintain physical function, strength, or endurance, reduce fatigue, and/or increase physical activity.

Among all strategies, strength training has shown the greatest results for increasing or at least maintaining the loss of muscle mass experienced during cachexia. However, while adding another stressor stimuli as physical exercise, it is recommended to implement it in combination with other non-pharmacological interventions, such as nutrition or supplementation, to address it from a multimodal point of view. Multimodal training (the combination of different physical training modalities, such as aerobic and strength exercises, with medication and/or nutritional supplementation) could be an interesting strategy to obtain better results.

Emotional Support

Emotional, psychological, or social support is an important component of multimodal interventions for cancer cachexia. Hypothesized or data-based benefits include alleviation of cachexia-related distress in patients and their family members, enabling stress management and coping in individual patients or patient–family member dyads, improving body image, improving quality of life, treating depression, and supporting adherence to exercise, physical activity, and nutritional care components of multimodal interventions.

Education is offered in most interventions with a psychosocial component. This education is about the cause of cancer cachexia and the management of its symptoms and related problems. Its purpose is to promote understanding to help the patient cope (emotionally and practically with the impact of cachexia) and thus to alleviate distress. Self-management education may also be included.

Emotional support, described as emotional counseling, is provided through methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy/cognitive reframing, motivational interviewing, mindfulness, therapeutic storytelling, a solution-focused strengths approach, supervised exercise, and relaxation techniques. Family members or informal carers are often involved and encouraged to learn about cancer cachexia alongside the patient, engage in self-management education and training, or enlisted as a co-worker to promote the intervention and monitor the patient’s behavior at home.

In summary, the management of cachexia requires a multifaceted approach incorporating nutritional interventions, medications and supplements, exercise, and emotional support. A combination therapy addressing the multiple underlying factors is more likely to be successful in treating this complex syndrome. Further research is needed to establish optimal treatment regimens.

Conclusion

Cachexia is a complex and debilitating condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of patients with chronic illnesses, particularly those with advanced cancer. Understanding the causes, risk factors, and symptoms of cachexia is crucial for early diagnosis and effective management. A comprehensive approach to treating cachexia involves a combination of nutritional interventions, medications, supplements, exercise, and emotional support tailored to the individual patient’s needs.

While there is currently no universally approved treatment for cachexia, ongoing research continues to explore promising therapies and interventions. By increasing awareness and understanding of this challenging condition, healthcare professionals can work together to improve the care and quality of life for patients suffering from cachexia. With continued advancements in research and a multidisciplinary approach to management, there is hope for better outcomes and support for those affected by this often-overlooked syndrome.