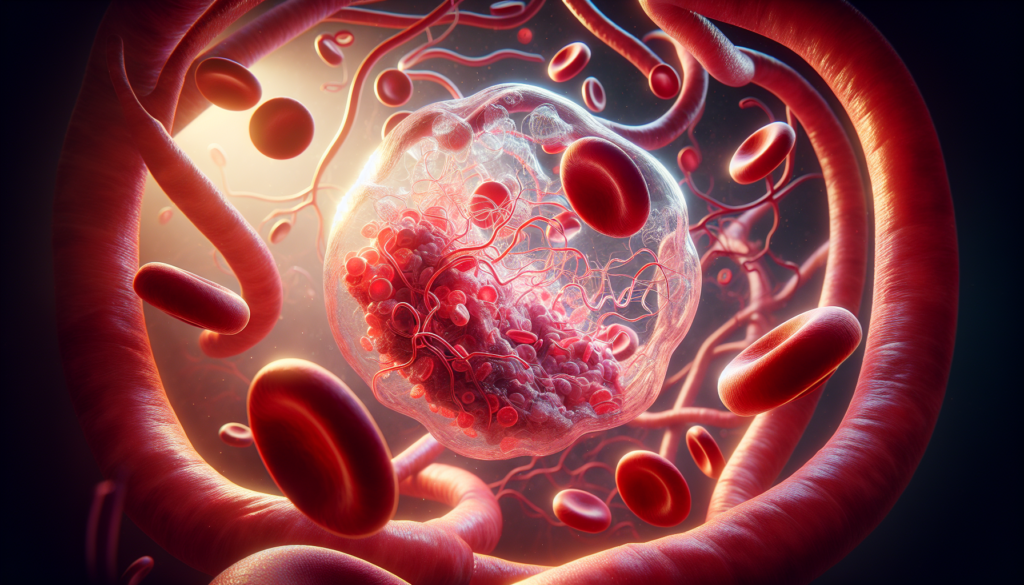

Thrombosis is a serious medical condition that occurs when blood clots form in blood vessels, potentially blocking blood flow to vital organs. This common yet dangerous health issue affects millions of people worldwide, leading to severe complications and even life-threatening situations. Understanding thrombosis is crucial for early detection, prevention, and proper management of the condition.

This article delves into the essential aspects of thrombosis, covering its underlying mechanisms, common types, and risk factors. It also explores strategies to assess and prevent thrombosis, as well as current management approaches. By shedding light on this important topic, readers will gain valuable insights to help them recognize, prevent, and address thrombosis-related concerns effectively.

The Pathophysiology of Thrombosis

The formation of thrombi involves a complex interplay between the endothelium, platelets, and coagulation factors. Under normal conditions, the endothelium provides an anticoagulant surface that prevents inappropriate clotting. However, various pathological processes can disrupt this delicate balance, leading to thrombosis.

Blood Clotting Process

The blood clotting process is initiated by damage to the endothelial lining of blood vessels. This exposes subendothelial tissue factor, which interacts with circulating factor VII to activate the extrinsic coagulation pathway. Simultaneously, endothelial damage triggers platelet adhesion and activation, releasing procoagulant factors and initiating the intrinsic coagulation pathway.

The activated coagulation cascades lead to the generation of thrombin, which converts fibrinogen into fibrin. Fibrin strands form a mesh that traps platelets, red blood cells, and other blood components, creating a stable clot. Factor XIIIa catalyzes the crosslinking of fibrin, further strengthening the clot structure.

RELATED: Phimosis: Causes, Symptoms, and the Best Treatment Methods

Virchow’s Triad

In 1856, Rudolf Virchow identified three key factors that contribute to thrombosis: endothelial injury, blood stasis, and hypercoagulability. This concept, known as Virchow’s triad, remains relevant today.

- Endothelial injury can result from various insults, such as smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. Damaged endothelium exposes subendothelial tissue factor and promotes platelet adhesion and activation.

- Blood stasis, caused by immobility, venous insufficiency, or atrial fibrillation, allows for the accumulation of procoagulant factors and platelets, increasing the risk of thrombosis.

- Hypercoagulability refers to an increased tendency for blood to clot due to genetic or acquired factors that disrupt the balance between procoagulant and anticoagulant mechanisms.

Hypercoagulable States

Hypercoagulable states can be inherited or acquired. Inherited thrombophilias include deficiencies in natural anticoagulants (antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S) and gain-of-function mutations (factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A).

Acquired hypercoagulability is more common and can result from various conditions:

- Malignancy: Cancer cells express procoagulant factors and interact with the endothelium, promoting thrombosis.

- Pregnancy: Hormonal changes and venous stasis increase the risk of thrombosis.

- Medications: Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and certain chemotherapeutic agents can induce a hypercoagulable state.

- Inflammation: Inflammatory conditions, such as autoimmune disorders and sepsis, activate the coagulation cascade and increase thrombotic risk.

- Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT): Antibodies against heparin-platelet factor 4 complexes can paradoxically cause thrombosis.

Understanding the complex pathophysiology of thrombosis is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies. By targeting the various components of Virchow’s triad and addressing hypercoagulable states, clinicians can reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with thrombotic disorders.

Common Types of Thrombosis

Thrombosis can occur in various parts of the body, leading to different clinical manifestations. The most common types of thrombosis are deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and arterial thrombosis.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms within the deep veins, usually in the legs. Symptoms may include swelling, pain, warmth, and redness in the affected limb. Risk factors for DVT include prolonged immobility, surgery, trauma, pregnancy, obesity, and inherited or acquired thrombophilia. If left untreated, DVT can lead to serious complications such as pulmonary embolism.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when a blood clot, often originating from a DVT, travels through the bloodstream and lodges in the pulmonary arteries. This can cause a sudden onset of symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, and cough. PE is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment to prevent life-threatening complications. Risk factors for PE are similar to those of DVT, and the two conditions often coexist.

Arterial thrombosis refers to the formation of blood clots within the arteries, which can lead to a reduction or blockage of blood flow to vital organs. The most common sites of arterial thrombosis are the coronary arteries (leading to myocardial infarction or heart attack) and the cerebral arteries (leading to ischemic stroke). Symptoms depend on the location of the clot and the organ affected. Risk factors for arterial thrombosis include atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hyperlipidemia.

Understanding the different types of thrombosis and their associated risk factors is crucial for early detection, prevention, and appropriate management. Prompt recognition and treatment can significantly reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with these conditions.

Risk Assessment and Prevention

Effective prevention of thrombosis relies on identifying individuals at high risk and implementing appropriate prophylactic measures. By assessing risk factors and adopting lifestyle modifications, the incidence of thrombotic events can be significantly reduced.

Identifying High-Risk Individuals

Several factors contribute to an increased risk of developing thrombosis. These include:

- Advanced age (over 60 years)

- Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2)

- Prolonged immobility or sedentary lifestyle

- Personal or family history of thrombosis

- Pregnancy and the postpartum period

- Hormone therapy (oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy)

- Chronic medical conditions (cancer, heart disease, respiratory disorders, or inflammatory diseases)

- Recent surgery, trauma, or hospitalization

Individuals with one or more of these risk factors should be closely monitored and considered for thrombosis prophylaxis.

RELATED: Pruritus: Detailed Guide on Causes and Treatments

Lifestyle Modifications

Adopting a healthy lifestyle can help reduce the risk of thrombosis. Key lifestyle modifications include:

- Maintaining a healthy weight through a balanced diet and regular physical activity

- Engaging in regular exercise to promote circulation and prevent blood stagnation

- Avoiding prolonged periods of immobility, such as during long-distance travel

- Staying hydrated by drinking adequate amounts of water

- Quitting smoking, as it can damage blood vessels and increase the risk of clot formation

- Managing chronic medical conditions effectively through proper treatment and follow-up

Encouraging patients to make these lifestyle changes can significantly lower their risk of developing thrombosis.

Prophylactic Measures

In addition to lifestyle modifications, prophylactic measures play a crucial role in preventing thrombosis, especially in high-risk individuals. These measures include:

- Mechanical prophylaxis:

- Graduated compression stockings: These stockings apply gentle pressure to the legs, promoting blood flow and reducing the risk of clot formation.

- Intermittent pneumatic compression devices: These devices use inflatable sleeves to compress the legs, mimicking the action of walking and improving circulation.

- Pharmacological prophylaxis:

- Anticoagulant medications: Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs), unfractionated heparin, or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) can be prescribed to prevent blood clotting.

- Aspirin: In some cases, low-dose aspirin may be recommended for its antiplatelet effects.

The choice of prophylactic measures depends on the individual’s risk profile, contraindications, and personal preferences. Healthcare providers should assess each patient’s thrombosis risk and develop a personalized prevention plan.

Regular monitoring and follow-up are essential to ensure the effectiveness of prophylactic measures and to detect any potential complications early. Patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of thrombosis and encouraged to seek medical attention promptly if they suspect a problem.

By identifying high-risk individuals, promoting lifestyle modifications, and implementing appropriate prophylactic measures, the incidence of thrombosis can be significantly reduced. A proactive approach to thrombosis prevention can improve patient outcomes, reduce healthcare costs, and save lives.

Management Strategies for Thrombosis

The management of thrombosis involves a multifaceted approach that includes acute treatment, long-term anticoagulation therapy, and ongoing monitoring and follow-up care. The primary goals of treatment are to prevent the extension and recurrence of the thrombus, reduce the risk of complications such as pulmonary embolism, and minimize the long-term sequelae of thrombosis.

Acute Treatment Approaches

- Anticoagulation therapy: The cornerstone of acute treatment for thrombosis is anticoagulation therapy. Heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) are commonly used for initial anticoagulation. These medications work by inhibiting the coagulation cascade and preventing further clot formation. The choice of anticoagulant depends on factors such as the patient’s renal function, bleeding risk, and the presence of comorbidities.

- Thrombolytic therapy: In certain cases, such as extensive iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability, thrombolytic therapy may be considered. Thrombolytic agents, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), work by dissolving the clot and restoring blood flow. However, thrombolytic therapy carries a higher risk of bleeding complications and is reserved for select patients.

- Mechanical interventions: In some situations, mechanical interventions may be necessary to manage thrombosis. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters can be placed to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients with contraindications to anticoagulation or recurrent thrombosis despite adequate anticoagulation. Catheter-directed thrombolysis or thrombectomy may be considered for extensive iliofemoral DVT to reduce the risk of post-thrombotic syndrome.

RELATED: Osteopenia Explained: From Diagnosis to Effective Treatment

Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy

- Oral anticoagulants: Following the acute phase of treatment, patients are typically transitioned to oral anticoagulants for long-term secondary prevention. Vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, have been the mainstay of long-term anticoagulation for many years. However, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have emerged as effective and more convenient alternatives. DOACs have a predictable anticoagulant effect, require less monitoring, and have fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

- Duration of anticoagulation: The duration of long-term anticoagulation depends on the underlying cause of thrombosis and the patient’s risk factors for recurrence. For provoked thrombosis, such as that occurring after surgery or trauma, a minimum of three months of anticoagulation is generally recommended. For unprovoked thrombosis or thrombosis associated with persistent risk factors, such as cancer or inherited thrombophilia, extended or indefinite anticoagulation may be necessary.

- Assessing bleeding risk: When considering long-term anticoagulation, it is important to assess the patient’s risk of bleeding. Factors such as advanced age, a history of bleeding, concomitant medications, and comorbidities can increase the risk of bleeding complications. Tools such as the HAS-BLED score can help stratify bleeding risk and guide decision-making regarding the duration and intensity of anticoagulation.

Monitoring and Follow-up Care

- Monitoring anticoagulation: Patients on long-term anticoagulation require regular monitoring to ensure therapeutic efficacy and minimize the risk of bleeding complications. For patients on warfarin, international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring is necessary to maintain a therapeutic range, typically between 2.0 and 3.0. DOACs do not require routine monitoring, but renal function should be assessed periodically to ensure appropriate dosing.

- Assessing for complications: During follow-up visits, patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of recurrent thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post-thrombotic syndrome. Post-thrombotic syndrome, characterized by chronic pain, swelling, and skin changes in the affected limb, can occur in up to 50% of patients following DVT. Compression stockings and exercise may help alleviate symptoms and prevent progression.

- Patient education and adherence: Patient education is crucial for successful long-term management of thrombosis. Patients should be informed about the importance of adherence to anticoagulation therapy, the signs and symptoms of recurrent thrombosis and bleeding complications, and the need for regular follow-up. Strategies to improve medication adherence, such as pill organizers and reminder systems, should be encouraged.

In summary, the management of thrombosis requires a comprehensive approach that includes acute treatment, long-term anticoagulation, and ongoing monitoring and follow-up care. The choice of anticoagulant, duration of therapy, and monitoring strategies should be individualized based on the patient’s risk factors, comorbidities, and preferences. Close collaboration between healthcare providers and patients is essential to optimize outcomes and minimize complications.

Conclusion

Thrombosis poses a significant health challenge, with far-reaching effects on individuals and healthcare systems worldwide. This complex condition, characterized by the formation of blood clots in blood vessels, has an impact on millions of lives and requires a comprehensive approach to manage effectively. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, identifying risk factors, and implementing preventive strategies are crucial steps to reduce the burden of thrombosis and its associated complications.

The management of thrombosis involves a multifaceted approach, combining acute treatment, long-term anticoagulation, and ongoing monitoring. By tailoring treatment plans to individual patient needs and risk profiles, healthcare providers can optimize outcomes and minimize complications. Continued research and advancements in thrombosis prevention and treatment hold promise to improve patient care and quality of life. Ultimately, raising awareness about thrombosis and promoting proactive measures to prevent its occurrence are key to reducing its impact on global health.