Trichomoniasis is a common sexually transmitted infection that affects millions of people worldwide. Caused by a microscopic parasite called Trichomonas vaginalis, this condition can cause uncomfortable symptoms and has an impact on reproductive health. Despite its prevalence, many individuals remain unaware of its existence or the potential consequences it may have on their well-being.

This article aims to shed light on the key aspects of trichomoniasis, including its symptoms, causes, and available treatments. Readers will gain insights into the basics of the infection, how it presents clinically, and the underlying pathophysiology. Additionally, the article will explore comprehensive diagnostic methods, effective management strategies, and essential prevention measures to control the spread of trichomoniasis.

Trichomoniasis Basics

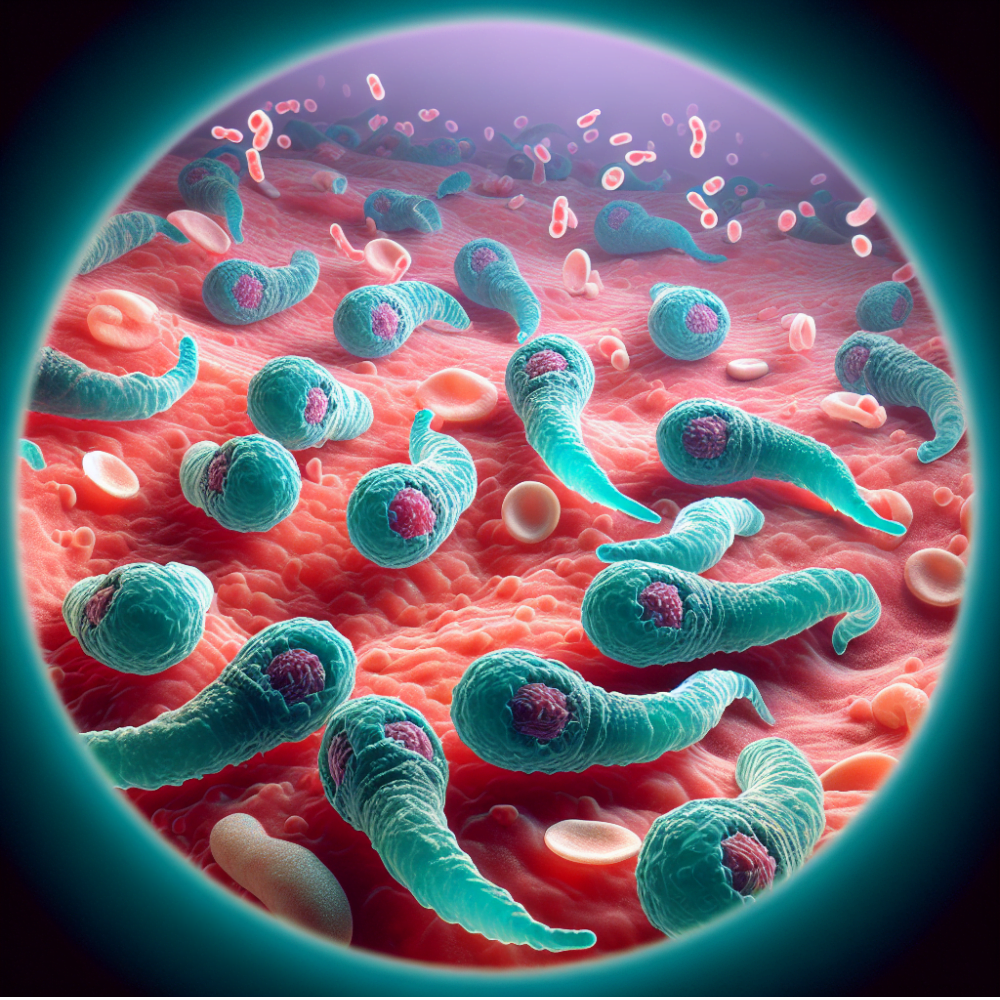

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated parasitic protozoan that causes trichomoniasis, a common sexually transmitted infection (STI). As an obligate parasite, it exists only as a trophozoite and does not form a cyst. The parasite is variable in size and shape, typically measuring 10 to 28 micrometers long and 5 to 12 micrometers wide. It possesses four anterior flagella and a recurrent fifth flagellum attached to the body by an undulating membrane, resulting in a distinctive quivering motility.

RELATED: Starting the AIP (Autoimmune Protocol) Diet: Essential Tips for Beginners

Definition and classification

T. vaginalis belongs to the phylum Parabasalia, which includes other anaerobic flagellated parasites. The parasite has a large genome of approximately 176 million base pairs, organized into six chromosomes and encoding around 60,000 protein-coding genes. T. vaginalis reproduces by longitudinal binary fission while preserving the nuclear membrane during the process.

Historical perspective

The discovery of T. vaginalis dates back to 1836 when French physician Alfred Francois Donné first observed motile microorganisms in the purulent vaginal discharge of infected women. However, it was not until 1916 that German physician Hohne described trichomoniasis as a clinical entity. Despite these early findings, research on this organism did not fully commence until the 20th century.

Epidemiological trends

Trichomoniasis represents a significant global health burden, with an estimated 156 million new cases occurring among people aged 15-49 years in 2020. The prevalence of T. vaginalis varies greatly by geography and risk group, with higher rates observed among persons of African descent and older women. In the United States, African American women have rates of trichomoniasis that are ten times higher than those of White women, highlighting a remarkable health disparity.

Recent studies have revealed a two-type population structure of T. vaginalis worldwide, with type 1 being more easily detectable by common diagnostic procedures and potentially indicating symptomatic individuals with high parasite loads. Type 2, on the other hand, may require higher concentrations of drugs to achieve lethal effects on the parasite and could be linked to antibiotic resistance. The presence of a double-stranded RNA virus, commonly referred to as Trichomonas vaginalis virus, in a significant proportion of type 1 isolates suggests that this virus may modulate the pathogenicity of the parasite by altering the expression of cysteine proteinases and surface molecules.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of trichomoniasis varies between men and women, with most infections being asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur, they typically appear within 5 to 28 days after exposure to the parasite.

Typical symptoms

In women, the most common symptoms of trichomoniasis include:

- Thin, frothy, yellow-green or gray vaginal discharge with a strong, unpleasant odor

- Genital inflammation, including vaginal and vulvar erythema, itching, and irritation

- Dysuria (painful urination) and dyspareunia (painful intercourse)

- Lower abdominal discomfort

Men with trichomoniasis are often asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, they may experience:

- Urethral discharge

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency

- Penile irritation or itching

Atypical presentations

In some cases, trichomoniasis may present with atypical symptoms or signs, such as:

- Strawberry cervix: A red, spotted appearance of the cervix observed during a pelvic exam, more commonly seen on colposcopy than with the naked eye

- Urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis in men

Complications

Untreated trichomoniasis can lead to several complications, particularly in women:

- Increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm delivery, premature rupture of membranes, and low birth weight infants

- Increased risk of cervical cancer

- Facilitated transmission of other sexually transmitted infections, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, and human papillomavirus (HPV)

In men, complications are less common but may include:

- Urethritis

- Prostatitis

- Epididymitis

- Infertility

Given the potential for asymptomatic infections and the risk of complications, it is essential for healthcare providers to maintain a high index of suspicion for trichomoniasis, particularly in high-risk populations, and to offer appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment.

Pathophysiology of Infection

Trichomonas vaginalis is an extracellular parasite that colonizes the human urogenital tract. It adheres to the epithelial lining of the vagina, cervix, urethra, and prostate to establish infection. The parasite’s pathogenicity is multifaceted, involving direct interactions with host tissues, modulation of the immune response, and factors that influence its virulence.

RELATED: Aplasia: Types, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

Host-parasite interaction

T. vaginalis undergoes a transformation from a free-swimming trophozoite form to an amoeboid form upon contact with host epithelial cells. This morphological change results in increased surface area contact, facilitating the parasite’s adherence to host cells and tissues. The parasite’s surface is coated with lipophosphoglycan (LPG), which plays a crucial role in host cell attachment by binding to galectin-1, a host cell receptor.

In addition to LPG, several other surface proteins, such as adhesins, BspA-like proteins, and GP63-like proteins, have been implicated in the parasite’s adherence to host cells. These proteins are differentially expressed among T. vaginalis strains, contributing to variations in their adherence capabilities and virulence.

Once attached, T. vaginalis can induce cytotoxicity in host cells through various mechanisms, including direct contact, secretion of proteases, and phagocytosis of host cells. The parasite’s cysteine proteases have been shown to degrade host proteins, disrupt cell junctions, and induce apoptosis in vaginal epithelial cells.

Immune response

T. vaginalis infection elicits both innate and adaptive immune responses in the host. The parasite’s LPG and other surface molecules are recognized by host pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), triggering the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

The initial innate immune response involves the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and natural killer cells to the site of infection. These cells secrete cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, which contribute to inflammation and the activation of adaptive immunity.

However, T. vaginalis has evolved mechanisms to evade and modulate the host immune response. The parasite can degrade immunoglobulins, complement proteins, and cytokines through its proteases. Additionally, it can induce apoptosis in immune cells and downregulate the expression of TLRs on host cells, thereby suppressing the immune response.

Factors affecting virulence

Several factors influence the virulence of T. vaginalis, including the parasite’s strain, the host’s immune status, and the presence of other microorganisms in the urogenital tract.

Different strains of T. vaginalis exhibit varying levels of adherence, cytotoxicity, the primary drug used for treatment. These differences in virulence have been attributed to variations in the expression of surface proteins, proteases, and other virulence factors.

The host’s immune status also plays a significant role in determining the outcome of T. vaginalis infection. Immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV, are more susceptible to severe and persistent infections.

The presence of other microorganisms in the urogenital tract, such as bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis or sexually transmitted pathogens like Mycoplasma hominis, can influence the virulence of T. vaginalis. These co-infections may create a more favorable environment for the parasite’s growth and enhance its pathogenic effects.

In conclusion, the pathophysiology of T. vaginalis infection involves a complex interplay between the parasite’s virulence factors, host immune response, and the urogenital microenvironment. Understanding these interactions is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent, diagnose, and treat trichomoniasis.

Comprehensive Diagnosis

Diagnosing trichomoniasis involves a combination of patient history, physical examination, and laboratory investigations. Healthcare providers must maintain a high index of suspicion for trichomoniasis, particularly in high-risk populations, and offer appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment.

Patient history and examination

A thorough patient history should include questions about symptoms, sexual history, and risk factors for trichomoniasis. Women with trichomoniasis may present with symptoms such as:

- Thin, frothy, yellow-green or gray vaginal discharge with a strong, unpleasant odor

- Genital inflammation, including vaginal and vulvar erythema, itching, and irritation

- Dysuria (painful urination) and dyspareunia (painful intercourse)

- Lower abdominal discomfort

Men with trichomoniasis are often asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, they may experience:

- Urethral discharge

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency

- Penile irritation or itching

During a physical examination, healthcare providers should look for signs of trichomoniasis, such as vaginal discharge, genital inflammation, and the presence of a “strawberry cervix” (a red, spotted appearance of the cervix) in women.

Laboratory investigations

Several laboratory tests can be used to diagnose trichomoniasis:

- Wet mount microscopy: This is the most common and cost-effective diagnostic test. A sample of vaginal discharge or urethral secretions is examined under a microscope for the presence of motile trichomonads. However, the sensitivity of this test is only 40-60%.

- Culture: Broth culture is considered the gold standard for diagnosing trichomoniasis. It has a higher sensitivity than wet mount microscopy, but results may take 2-7 days.

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs): These tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have high sensitivity and specificity for detecting T. vaginalis DNA. NAATs are becoming increasingly popular for diagnosing trichomoniasis.

- Rapid antigen tests: These tests detect T. vaginalis antigens in vaginal fluid samples and can provide results within 15 minutes. They are less sensitive than NAATs but more sensitive than wet mount microscopy.

Point-of-care testing

Point-of-care (POC) tests for trichomoniasis have been developed to provide rapid, on-site diagnosis. One example is the OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test, an immunochromatographic assay that detects T. vaginalis antigens in vaginal swabs. POC tests offer several advantages:

- Rapid results (within 10-15 minutes)

- Easy to use and interpret

- Can be performed by healthcare providers with minimal training

- Facilitate immediate treatment and partner notification

However, POC tests may have lower sensitivity compared to laboratory-based tests, and negative results should be confirmed with more sensitive methods if clinical suspicion remains high.

In conclusion, a comprehensive approach to diagnosing trichomoniasis involves considering patient history, physical examination findings, and appropriate laboratory investigations. The development of sensitive and specific POC tests has the potential to improve the diagnosis and management of this prevalent sexually transmitted infection.

Management Strategies

The management of trichomoniasis involves a combination of pharmacological interventions and non-pharmacological approaches. Treatment strategies may vary for special populations, such as pregnant women and individuals with drug allergies or resistance.

Non-pharmacological approaches

Non-pharmacological approaches play a supportive role in managing trichomoniasis:

- Abstinence from sexual activity during treatment to prevent reinfection

- Condom use to reduce the risk of transmission

- Vaginal pH acidification using boric acid or other acidifying agents

These approaches can be used in conjunction with pharmacological interventions to enhance treatment outcomes and prevent recurrence.

Prevention and Control

Trichomoniasis has an impact on reproductive health and is the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide. Prevention and control strategies for trichomoniasis include barrier methods, behavioral interventions, and vaccine development prospects.

Barrier methods

The best way to prevent trichomoniasis and other STIs among sexually active individuals is through consistent and correct use of condoms (external or internal) during penile-vaginal, oral, and anal sex. Partners of circumcised men may have a somewhat reduced risk of T. vaginalis infection compared to those of uncircumcised men. Douching is not recommended as it might increase the risk for vaginal infections, including trichomoniasis.

Behavioral interventions

Primary care physicians play a crucial role in evaluating a patient’s risk of contracting STIs by conducting an inclusive and comprehensive sexual health history. Key elements include assessing an individual’s sexual orientation, frequency of sexual activity, number of partners, and type of sexual engagement (e.g., penile-vaginal intercourse, oral sex, anal sex). Numerous national organizations recommend that physicians periodically obtain a sexual history or sexual risk assessment and discuss risk reduction with all patients.

RELATED: Understanding Aphonia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

Vaccine development prospects

Currently, no vaccine is available to prevent trichomoniasis. However, vaccine development is an important area of research due to the high global prevalence of trichomoniasis and its associated adverse health outcomes, such as preterm birth, cervical cancer, prostate cancer, and increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission. Challenges in vaccine development include the lack of naturally acquired immunity to the infection, the parasite’s ability to evade host immune responses, and limited robust animal models to study the infection. Despite these challenges, researchers are working on identifying potential vaccine targets and exploring novel technological approaches to advance vaccine development for trichomoniasis.

In conclusion, the prevention and control of trichomoniasis rely on a combination of barrier methods, behavioral interventions, and the prospect of future vaccine development. Healthcare providers play a vital role in assessing risk factors, providing education, and offering appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment to reduce the burden of this prevalent STI.

Conclusion

Trichomoniasis has a significant impact on reproductive health worldwide, affecting millions of people. This article has shed light on the key aspects of this common sexually transmitted infection, from its basic biology to comprehensive diagnosis and management strategies. Understanding the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and available treatments is crucial to address this prevalent health issue effectively.

To wrap up, the prevention and control of trichomoniasis rely on a mix of barrier methods, behavioral changes, and potential future vaccines. Healthcare providers play a vital role in assessing risk factors, educating patients, and offering appropriate testing and treatment. By raising awareness and implementing effective strategies, we can work towards reducing the burden of this widespread STI and improving overall sexual health globally.